Welcome to Week 12 of my slow-read of Crime and Punishment. This week’s chapter is Part Two, Chapter 5.

Please bookmark the homepage for the read-along. Here, you’ll find links to everything you need as we read the novel together.

Request a Translation Comparison

Paid subscribers may request translation comparisons for anything that jumps out in whatever translation you’re reading.

Once requested, it will be added to the public translation comparison spreadsheet.

If you enjoy this content and would like to help me to keep it going, please consider a paid subscription.

Thank you. 🙏🏻

This week’s characters

Characters in this week’s chapter in the order that they are mentioned. Raskolnikov isn’t mentioned because he’s pretty much in every chapter:

Luzhin • Zosimov • Razumikhin • Nastasya

Part Two, Chapter 5 Synopsis

All quotations in this post are taken from Roger Cockrell’s translation of 2022, Alma Classics, © Roger Cockrell 2022

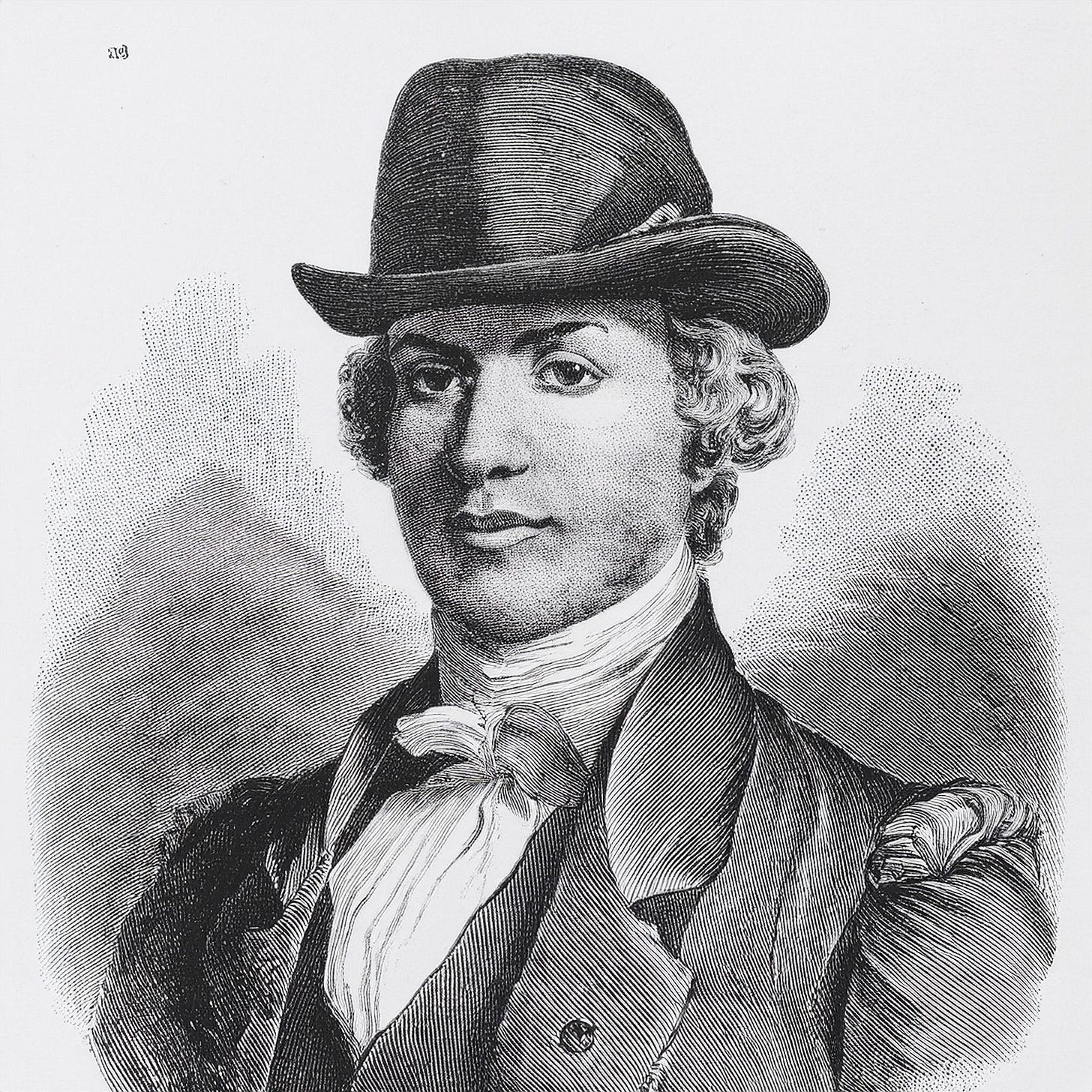

The stranger who appeared at the door at the end of the previous chapter was none other than Pyotr Petrovich Luzhin. Raskolnikov seems agitated, as if expecting another police officer, so when Luzhin introduces himself, Raskolnikov stares at him as if hearing the name for the first time. Luzhin is taken aback, clearly expecting to have been recognized by virtue of Raskolnikov’s mother’s letter. Razumikhin puts him somewhat at ease, after which Raskolnikov checks Luzhin over and we are given a long description of his appearance.

Luzhin informs Raskolnikov that he has rented rooms for his mother and sister. Not nice rooms, as it turns out. He’s also renovating an apartment for himself and Dunya after their wedding, but is now staying with Lebezyatnikov. Raskolnikov has to think where he’s heard that name before. Luzhin says he was Lebezyatnikov’s guardian once… ‘a very nice young man … and well-informed, as well … I much enjoy meeting young people: you can learn all the latest things from them.’

This reminds me of what Raskolnikov’s mother wrote in her letter about Luzhin’s sharing ‘the convictions of today’s generation of young people.’

It’s an interesting idea, about keeping up with the latest ideas by living in the city. Even in today’s fast-paced information age, it can still feel a bit like that. The fawcet of news and media is there, but it can be turned off if one so chooses. It’s harder to do that in cities. I live in a small village on a Scottish island, so my experience is very much one of being able to switch off to some degree if I want to. My daughter, aged 20, is in higher education in London, so she’s very much exposed to ‘all these innovations, reforms, new ideas…’ Although I suppose that would apply at any kind of higher educational institution. Remember that Raskolnikov and Razumikhin are both students. Are not they exposed to these ideas? See this clash of ideas between Luzhin and Razumikhin.

Luzhin states that being closer to the younger generation ‘makes him very happy. It seems to me I can find much clearer views on things, together with better, so to speak, critical judgement, and a greater spirit of enterprise…’

His ideas are at odds with Razumikhin’s.

‘You’re wrong, there’s no such spirit. […]It’s been almost two hundred years since we last embraced such a notion…’

There’s a lot in this exchange between the two men, where one is in favour of the new and the other is more in favour with traditions. Does that remind you of anything? Progressivism vs conseravatism. I guess politics ever was and ever will be divisive to some extent. Raskolnikov and Zosimov join in the debate. Luzhin uses the old metaphor of chasing two hares and catching none to illustrate the new, progressive ways of thinking. He appears to have misunderstood the concept of ‘love thy neighbour’, stating that if he did that, he’d tear his kaftan in half to give his neighbour half and they would both end up being half-naked. But he goes on to expound his ideas of altruistic enterprise. I’m reminded that Marmeladov talked of Lebezyatnikov’s having lent Lewes’s Physiology to his daughter. This was Physiology of Common Life (1859) by George Henry Lewes, translated into Russian in 1861 and widely read by the materialistically inclined generation of Russian young people in the 1860s.

Fellow Crime and Punishment Substack writer Dana Oljós has written about Lewes’ Physiology in her post below:

I had to laugh at this from Razumikhin:

"Forgive me, it looks like I'm one of those without much intelligence," Razumikhin interrupted brusquely, "so let's drop it. I began this discussion in earnest, but over the last three years I've become so sick and tired of all this self-congratulatory chit-chat, of all these endless, incessant platitudes, of the same thing over and over again, that I swear I blush even when I hear others talking such stuff. You, of course, are in a hurry to demonstrate how knowledgeable you are - I can quite understand this, and I'm not criticizing you for it. I simply wanted to find out what kind of a person you are, because, you see, so many shady characters have recently joined the progressive cause and have so distorted everything they have been in contact with, for their own self-interest, that the whole cause has been decidedly tarnished. Well, that's enough of that!"

It’s just so interesting to read dialogue like this from 1860s St Petersburg that could’ve been written in 2020s Britain (or USA or France or …)

There’s a clear division between Luzhin and, shall we say, Raskolnikov’s crew and that’s without the whole family situation that Raskolnikov is dealing with. Luzhin expresses to Raskolnikov that he looks forward to their acquaintance’s becoming stronger with his marriage to Dunya. Dostoyevsky has made it quite clear that, in Raskolnikov’s mind, that’s not going to happen.

Zosimov completely changes the subject by announcing that the murderer must have been known to the victim. Razumikhin agrees and mentions that Porfiry is questioning all of the victim’s clients. Razumikhin then goes on to explain why he thinks that the murderer was naïve and inexperienced rather than a cunning scoundrel, as some of the others in the room thought. ‘He may have known how to murder, but he had no idea how to rob!’

Luzhin butts in and expresses his thoughts on the rise in crime, both among the lower and upper classes. He blames it on the lack of enterprise. We’re back to that old chestnut. So he’s progressive in his politics with a belief in free-market economics and enterprise. His politics have a whiff of New Labour about them. Things can only get better.

Raskolnikov gets emotional and asks Luzhin why he considers the fact that his sister is destitute as a reason for her to be a good match. Luzhin replies that Raskolnikov’s mother has misunderstood him and is quite beside himself that such a misunderstanding could occur. Raskolnikov doesn’t take that well and threatens to throw him down the stairs if he ever speaks out against his mother again. Fair enough. They have an argument and Raskolnikov tells him to ‘go to hell’ right to his face. He then tells everyone else to leave because he wants to be alone. They have a discussion as they leave, and Zosimov notes that Raskolnikov seems to get more agitated whenever the murder is mentioned.

Raskolnikov is left with Nastasya. She offers him tea, but he declines and she leaves. He’s alone once again.

Thoughts

It’s a fast-moving chapter that reveals a lot about the politics of the day. It sets the scene well for the schism between Raskolnikov and Luzhin that’s sure to follow, with Dunya and Pulkheria Alexandrovna in the middle. I love the arguments that we get in this chapter, with Raskolnikov’s health playing less of a role than it has in the previous two chapters. It’s interesting that I see parallels between the politics of Imperial Russia and the present time, but that’s what’s so great about literature. People are people, so why should it be…1

Translation Points

I’ve copied out the quotation above which begins with Razumikin’s saying ‘forgive me’. It feels like a key moment in the chapter in conveying the politics of 1860s St Petersburg, and the differences between the city and the provinces.

The other seven translations are in the comparison spreadsheet.

Thank you for reading

Thank you for reading with me.

This book group is entirely funded by its readers. If you enjoy my posts, please consider a paid subscription to support me and this work.

Or if you’d rather just buy me a coffee, I’d be very grateful!