I started writing this on 12 September and then procrastinated on it. Not a great start. I think I’ve been feeling a bit intimidated. I feel like I should be some kind of expert to be leading a group through the humanities. But the point is that I’m not an expert. And neither do you have to be to follow along. I hope that in publishing these thoughts it will encourage you to pick up these texts and read them too. It doesn’t have to be at the same time as I’m reading them—nor could it be, as I’m already over a month behind on my own schedule—but whenever you’re ready and at your own pace.

I have two goals:

To learn and grow from reading the texts on Ted’s list;

To show others that these books are not intimidating.

Ted’s List

I do have some scholarly background, but when I got my Russian language and literature degree in the 90s, I wasn’t ready for the books that were on my reading lists. Now, in my 50s, I’m hungry for it. And that hunger is all I need. So when Ted published his list, I was like, ‘Yep! This is for me!’

Right, preamble done. Let’s look at the texts.

The Last Days of Socrates

All I knew of Socrates was what I learned from Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure, except that I did actually know it wasn’t pronounced as they pronounced it. Hands up those of you that still pronounce it that way for giggles? So Crates—dude!

The first thing I’ll say about The Last Days of Socrates is that I was surprised at how easy it was to read. I was expecting… I dunno, more Greek maybe? Ancient English with archaic vocabulary. But no—it was surprisingly readable. (I read Hugh Tredennick’s translation, Penguin Books, 2003 - affiliate link)

He has only one thing to consider in performing any action; that is, whether he is acting justly or unjustly, like a good man or a bad one.

I won’t go through a description of what the book is about. This is a reading group, so I’m hoping that you’ve read it. I’d rather go through what notes I’ve taken and highlights I’ve made and talk about what I got out of it. I’ll also talk about how it feels as a newcomer to be reading these ancient texts.

I read Euthyphro out on the porch in the sunshine and probably was feeling a bit out of my depth. It took me some time to get into the rhythm and feel of the topics. What I do remember is going for a walk with the dog and my son after reading it and explaining to my son what it was about—the dog didn’t care. The basic premise was the question of whether something is holy because it is approved of by gods, or do the gods approve of it because it is holy; is the holiness innate or is it conferred? It begs the question.

Socrates: Come then, let’s examine our thesis: for any action, or person, if it is ‘divinely approved’ it is holy, and if it’s ‘divinely disapproved’ it is unholy; and they’re not the same, but exact opposites, the holy and the unholy. Is that it?

So, that’s the premise of Euthyphro, the first book of the four that make up The Last Days of Socrates.

In Apology, I’ve made this highlight.

He has only one thing to consider in performing any action; that is, whether he is acting justly or unjustly, like a good man or a bad one.

It made me think of my favourite line from The Way of Kings by Brandon Sanderson: ‘act with honor and honor will aid you.’

There’s a beautiful passage about being true to oneself, regardless of the consequences. Socrates supposes that he is acquitted but on the condition that he cease from philosophising. If caught breaching this condition, death would be the result. Here’s how he responds:

Well, supposing, as I said, that you should offer to acquit me on these terms, I should reply, 'Gentlemen, I am your very grateful and devoted servant, but I owe a greater obedience to God than to you; and so long as I draw breath and have my faculties, I shall never stop practising philosophy and exhorting you and indicating the truth for everyone that I meet. I shall go on saying, in my usual way, "My very good friend, you are an Athenian and belong to a city which is the greatest and most famous in the world for its wisdom and strength. Are you not ashamed that you give your attention to acquiring as much money as possible, and similarly with reputation and honour, and give no attention or thought to truth and understanding and the perfection of your soul?"

Anytus is of the opinion that by practising philosophy Socrates is corrupting the youth, and so he should cease forthwith. Socrates disagrees and would rather be put to death than cease from following his heart. It doesn’t feel like he’s being a martyr to his cause either—it’s not a fight; more like going with the flow. It’s feels like eastern philosophy in the style of Wu Wei rather than a belligerent refusal to go against his principles.

And then he says this:

Are you not ashamed that you give your attention to acquiring as much money as possible, and similarly with reputation and honour, and give no attention or thought to truth and understanding and the perfection of your soul?

I mean YES, right? I like to think that, by reading such texts as these, I’m giving my attention to the second part of that quotation—truth and understanding.

Crito

Crito feels that Socrates should attempt to escape for the sake of his family and friends. Crito worries what people will think of him if he doesn’t use his wealth to help Socrates escape, which leads to this:

But my dear Crito, why should we pay so much attention to what ‘most people’ think? The most sensible people, who have more claim to be considered, will believe that things have been done exactly as they have.

There’s a message for all of us there, I think. We do tend to dwell on what others might thing of us and, when you think about it, it’s all rather silly. This is why I feel that there is growth in creativity, following one’s heart and making something without any concern for how it is received or promoted by algorithms.

SOCRATES: At the same time I should like you to consider whether we still agree on this point: that the really important thing is not to live, but to live well.

CRITO: Agreed.

SOCRATES: And is it still agreed or not that to live well amounts to the same thing as to live honourably and justly?

‘Honourably and justly.’ Words to live by. Again, I’m reminded of the words of the Stormfather from Sanderson’s Way of Kings, and of Freemasonry. The second degree tools as applied to our morals teach us morality, equality and justness and uprightness of life and actions.

Socrates goes on to set out to Crito the ways in which he is bound by the laws of the state in which he is a resident, another area where I’m reminded of Freemasonry. In the first degree charge, Freemasons are bound to pay ‘due obedience to the laws of any State which may for a time become the place of your residence or afford you its protection; but, above all, by never losing sight of the allegiance due to the Sovereign of your native land, ever remembering that nature has implanted in your breast, a sacred and indissoluble attachment towards that country whence you derived your birth and infant nurture.’ It’s a contract, and to act against his contractual obligations towards the state would be to act unjustly, and Socrates is not about to do that.

Phaedo

The longest book of the four. It has me thinking of the third degree in Freemasonry, contemplating death and all it portends. Socrates states that, for the philosopher, death holds no fear. In fact it is a thing to which philosophers look forward.

He goes on to claim, in a discussion about how death is simply a splicing of the soul from the body, that the bodily senses during life are actually a hindrance to wisdom. Sight and hearing lie, or, rather, ‘are not clear and accurate.’, and as the other senses are inferior to sight and hearing, they can hardly be clear or accurate either. In a recent video interview I watched with author Joanne Harris, she recommended a book called Pieces of Light by Charles Fernyhough, in which the idea is posited that memory also lies. I have the book on my shelf to be read because it sounds super interesting. If that turns out to be true, then it sees that the soul—or the mind—is constantly being distracted from the truth, making the accumulation of wisdom difficult if not impossible. Is that what Socrates is saying? Seems a bit harsh to me and I don’t buy it. Although the memory thing seems perfectly plausible and I have an example of how that has shown up in my own narrative.

In fact, thinking about it, I’m reading these words with my eyes, using sight. The meaning behind the words is feeding my soul with philosophical ideas, leading me to ponder and deliberate their meaning and come to conclusions. These conclusions are based not only upon what I’m reading, but also on my life experience thus far, my education, my culture, my relationships, my feelings. So I reject the idea that one’s body is a distraction from the attainment of wisdom.

If no pure knowledge is possible in the company of the body, then either it is totally impossible to acquire knowledge, or it is only possible after death...

There’s a bit about wisdom that I’ve highlighted:

For let me tell you, gentlemen, that to be afraid of death is only another form of thinking that one is wise when one is not; it is to think that one knows what one does not know’.

It’s actually quite a comforting section. Why should we fear death when we don’t know what it entails? Socrates knows that he is facing a potential death sentence for his impiety, so it makes sense that he’s trying to be chill about it.

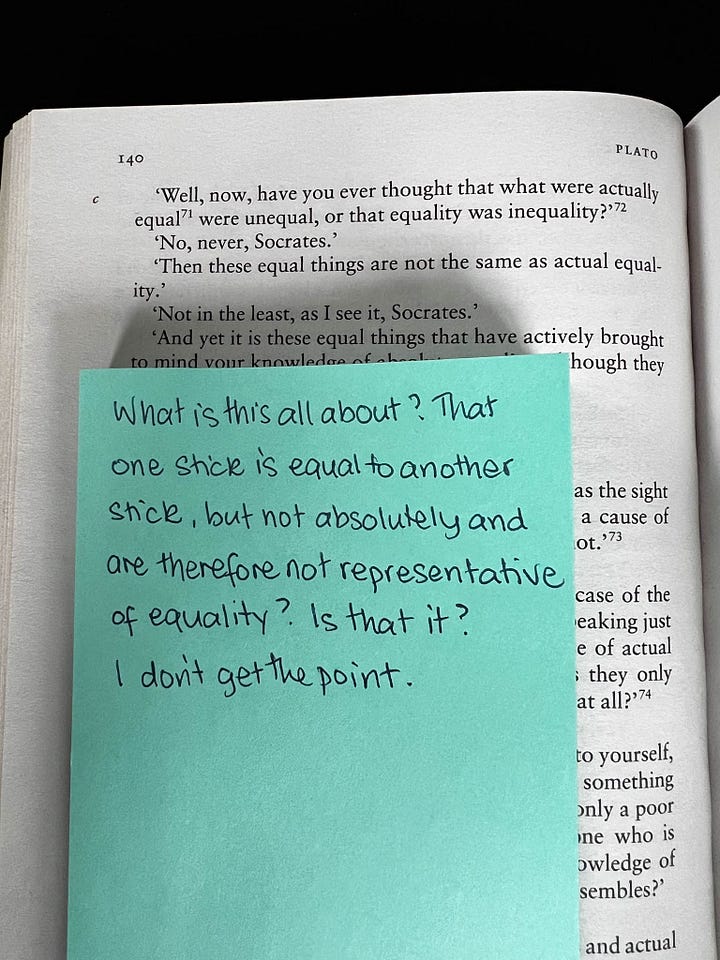

There’s a bit about EQUALITY in Phaedo that I’m not sure I properly understood. ‘Equal things are not the same as actual equality.’

Incidentally, I’m going to see ex-Genesis guitarist Steve Hackett playing highlights from the Lamb Lies Down on Broadway at the end of the week!

It goes on to discuss the idea that knowledge of equality must have been obtained before birth. I mean, what? Not only of equality, but of beauty itself, or goodness, justice, holiness—all those qualities. Then he says that we lose the knowledge that we had as soon as we are born and spend our lives recovering that knowledge through learning. Once again, I find myself thinking of a fantasy series, this time Robin Hobb’s Liveship Traders series and the relationship between the spoiler—see footnote.1

The notion that the body is a distraction from attaining wisdom continues.

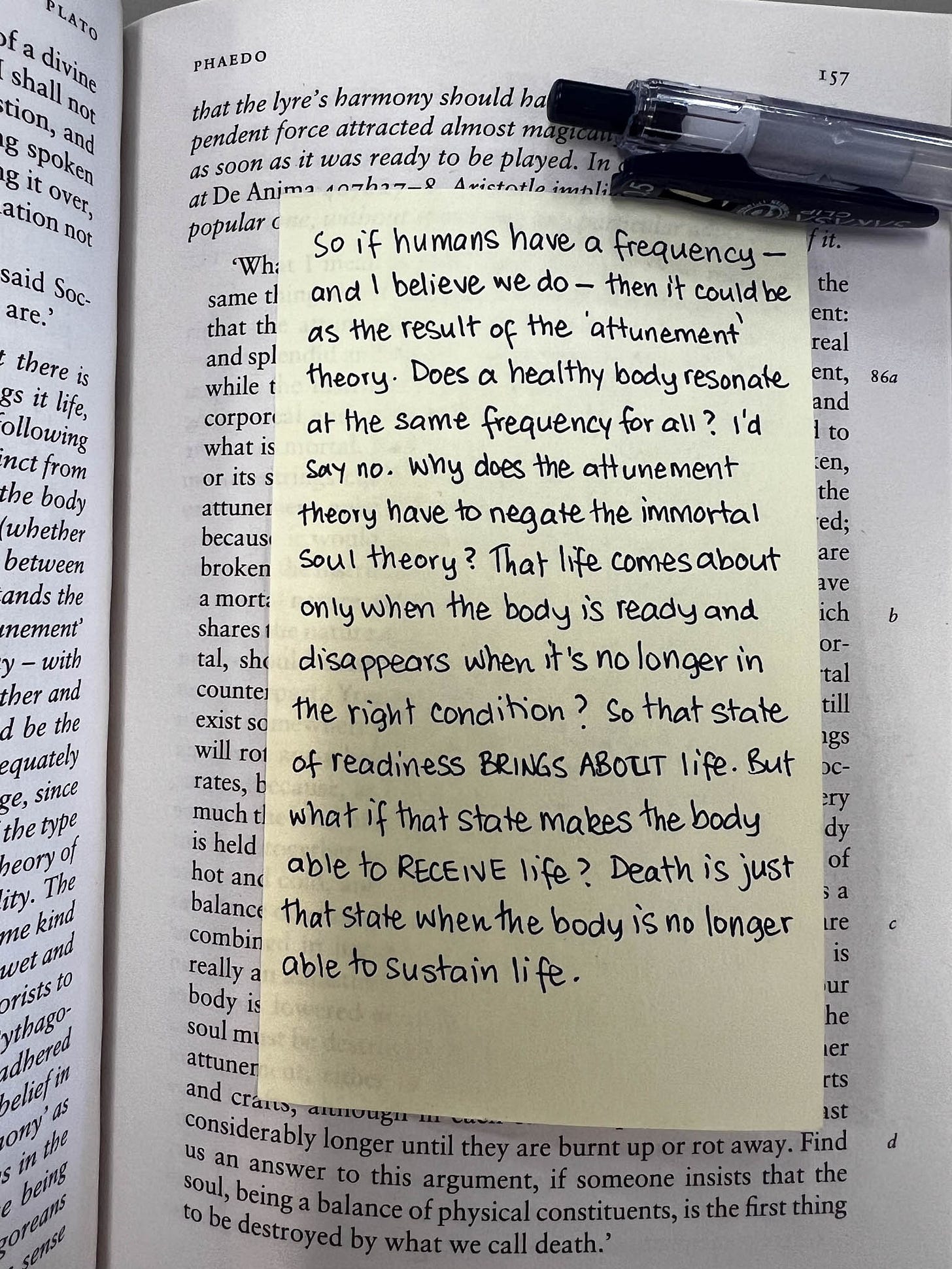

Attunement theory

Moving on from the body vs spirit idea, we have the attunement theory. Here’s a note I took on my first reading.

It’s a deep philosophical idea and I end up tying myself in knots when I think about it. I would imagine that whole books have been written on this idea. But, as a lover of the acoustic guitar, it’s an idea I find myself pondering. Okay, people aren’t guitars—or lyres—but frequency is an idea that, well, resonates with me. Simmias posits that when a stringed instrument is broken, that state of attunement—or the soul—does not simply disappear or die; it must go somewhere.

I find myself imagining a perfectly tuned guitar as being in a state of divinity, so that when that perfect state is achieved, magical things become possible. It actually has me wanting to watch Terrence Malick’s film The Tree of Life again to see that sequence that portrays life in such a profound way.

The way Phaedo is written seems to suggest that the soul is an entity in itself and, while it may exist independently of the body, it stays in the same form. But that’s not how I see it. My view is that the soul is a splinter taken from the universal that is placed in a body. For me, the idea of attunement is when we open ourselves up to the universe and we feel that we are at one. The word I’ve always used is harmony, another musically loaded term: attunement, harmony, frequency, resonance—these all fit my philosophical world view. Perhaps that comes from my being a musician, or perhaps I’m a musician because I feel those ideas in my soul. Who knows?

And I love how I see these ideas in my favourite fantasy series, such as the Liveship Traders and the Chronicles of Thomas Covenant the Unbeliever.

I’ll leave this essay here and possibly come back to The Republic in another one. Ted has only two books of The Republic on his list for week 1 for reasons of page count limitations (Books I, VII) but I read the whole book. It’s been a very enriching and rewarding experience and I’d love to know how you enjoyed these books as followers of this Substack. As I write this, I’m already deep into The Odyssey for month two, reading two different editions (Wilson and Fry) and have also bought a bunch of other books on Greek mythology. How will I ever tear myself away for the Analects in month three?

Links

These are affiliate links to the books mentioned in this post. Using these links to buy the books will earn a small commission for me at no cost to you. The links offer a choice of retailer, including Amazon links that are localised to your location where possible.

Last Days of Socrates, Plato, Penguin Classics, Hugh Treddenick, Harold Tarrant

Lord Foul’s Bane, Stephen Donaldson, Book 1, Chronicles of Thomas Covenant the Unbeliever

Liveships, serpents and dragons. This story uses memory as a plot device.

Thanks for posting this. I am following Ted’s course too and have been wondering how other people felt about the books. You seem to have enjoyed week 1 more than I did — I guess Plato is not my cup of tea.