Well, that was an interesting experience!

Crime and Punishment is one of my all-time favourite novels. The most surprising thing about it for me is how eminently readable it is. I don’t know if you’re the same, but it often feels that classic works of literature will be intimidating. Crime and Punishment is not. Nor for that matter is The Brothers Karamazov, which I’m currently reading with

. The same goes for War and Peace, which I read last year with , and Anna Karenina, which I’m reading this year with . On its surface, Crime and Punishment reads like a crime novel. But underneath there lurk hidden depths that reward multiple reads. There is as much to take from it today as there was in the 19th century.Speaking of Dana, when it comes to leading a group through Dostoyevsky’s novels, she’s the writer to go to. Her analyses of Crime and Punishment were so helpful that I felt like a bit of an impostor with my own posts. Okay, I know it’s not a competition and that my thoughts are as valid as anyone else’s, so I should cut myself some slack. But the way Dana shared her knowledge—and accompanying artwork—really brought the novel to life. You still have time to catch up with her group reading of Karamazov if you fancy giving another Dostoyevsky classic a go—and you really should!

Crime and Punishment is a novel that places mental health front and centre, and that’s perhaps what makes it a favourite of mine. I can’t say what diagnosis Raskolnikov might be given were he to be assessed by modern science, but what I do enjoy about this novel is that Dostoyevsky explores this character’s arc and redemption through philosophy and religion. I find that incredibly helpful and is a big reason why I’m in favour of the epilogue to this novel. I’ve read that many critics consider the epilogue to be tacked on and say that it should be ignored. I don’t agree with that. For me, it’s about redemption through love. There are instances throughout the novel where Raskolnikov tries hard to avoid humanity, but we’re told by the narrator that he actually seeks human connection. I feel the same way myself, so the epilogue gives me hope that, if I keep working towards my goal of universal love, it will eventually pay off. Raskolnikov’s plan to rid the world of an evil moneylender for the good of humanity was misplaced. Universal love includes evil moneylenders as well as everybody else. His ‘punishment’ illustrates that through the whole novel and it begins long before he even commits the crime. But his confession and later his love of Sonya save his soul from its torment. He gives up fighting and just lets go, as if to be reborn.

This could well have formed the basis for a new story, but our present story has now come to an end.

Thanks for joining me on the this read-along.

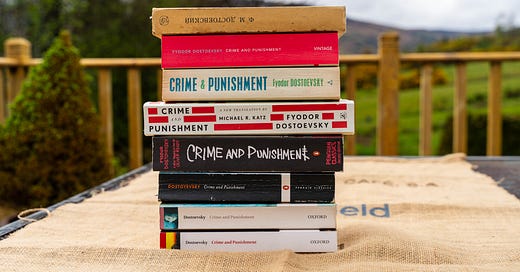

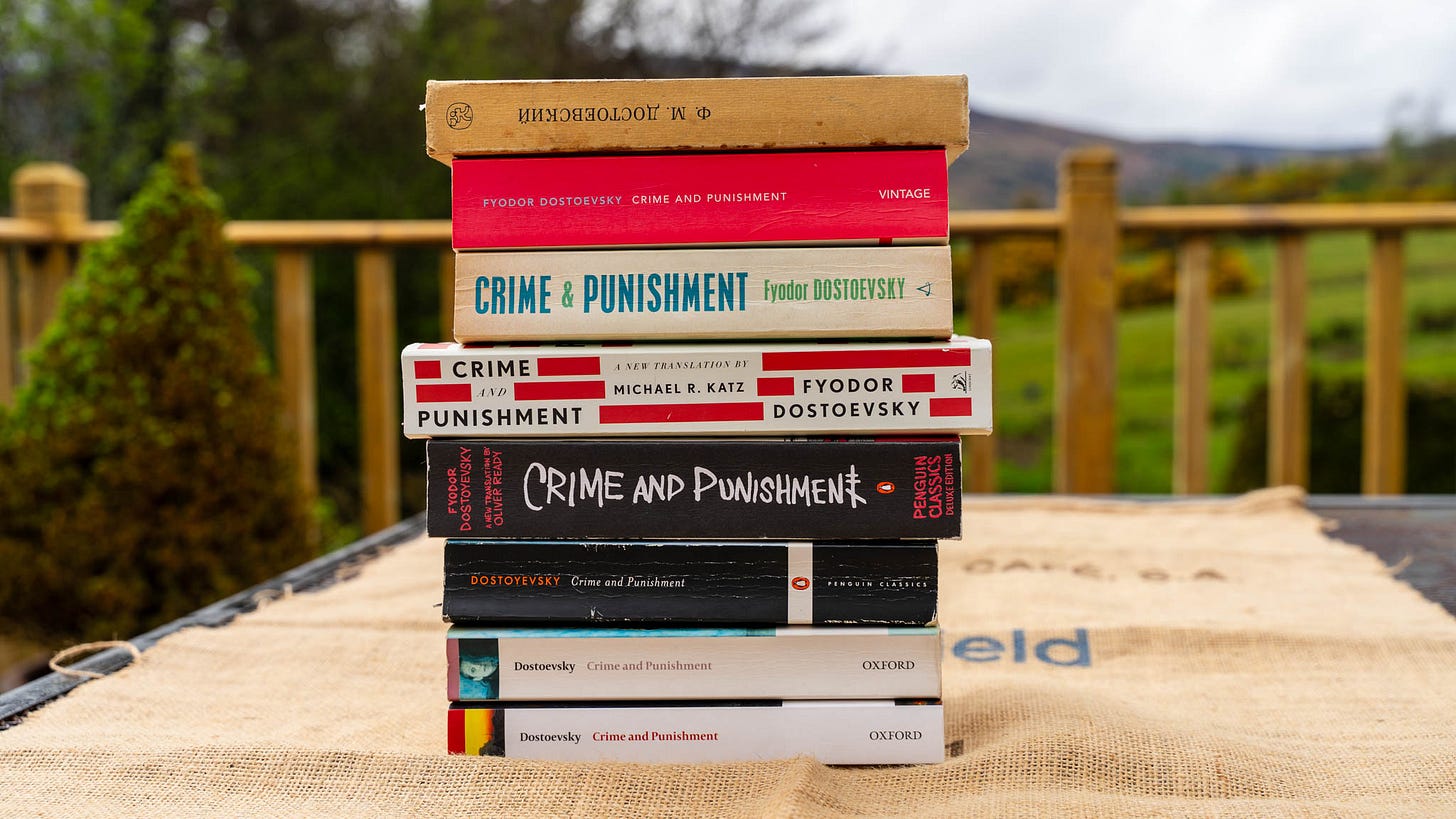

Translations

It has been very interesting indeed to compare eight different translations of Crime and Punishment. Choosing a translation is always a tricky thing and, in some ways, it can come down to personal preference. There is no such thing as a perfect translation or a literal translation; something will always be lost in the process. I wrote about an ideal example to illustrate this near the beginning of this process when I discussed the various translations of Tsar Gorokh in this post.

I kept the translation comparison spreadsheet going throughout with an example from almost every chapter, so if you’re wondering which translation you might prefer, it’s a helpful resource.

But if you just want to buy the one I recommend, get the Roger Cockrell translation.

Thanks again for all the work you put in and please don't consider yourself an imposter. What you wrote was very clear and approachable and that is worth a lot. And now on to new literary adventures!