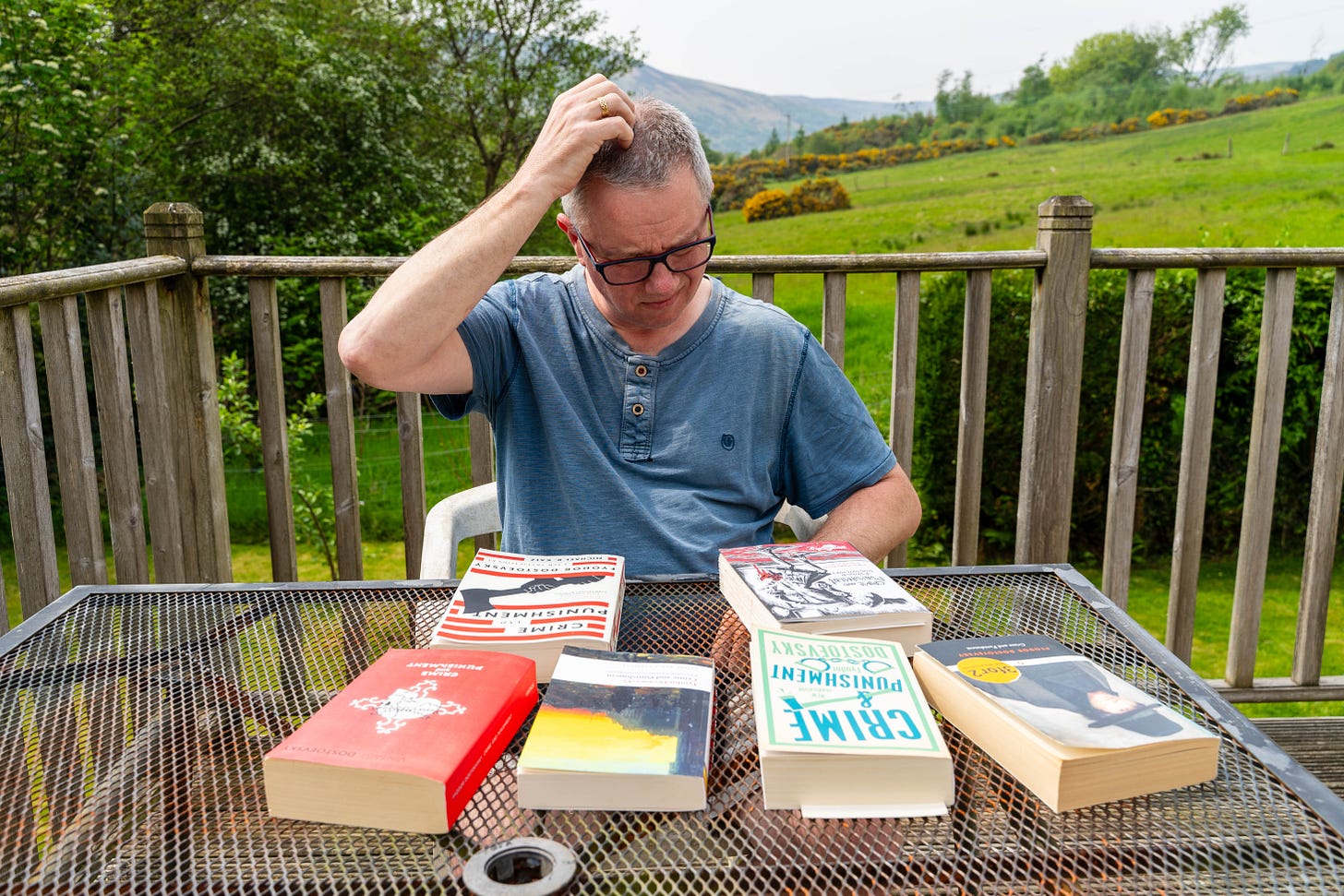

Which Translation Do I Choose?

Comparing Eight Translations of Crime and Punishment

Choosing a translation of a foreign classic can be a difficult choice. You might be wondering why there are so many. There are currently fourteen published translations of Crime and Punishment into English that I know of, starting with Frederick James Wishaw’s translation of 1886—the same year as the novel’s publication—through to the most recently pub…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Cams Campbell Reads to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.