It’s the first day of our group read of Oblomov by Ivan Goncharov, first published in 1959. The format’s probably going to be more video-based than written, because I’ve learned through my Crime and Punishment project that I’m more likely to procrastinate, although the video-making could serve as a way in for written content as well. We shall see.

I’ve worked out that I’ll need to read a chapter a day when possible in order to stick to the planned schedule of finishing the novel in two months. Part One has eleven chapters, and part two twelve, so to complete part one by the end of May will mean basically a chapter a day when I can with a few travelling days and recovery days built in. So quick recordings after each chapter seems like the way to go, with written content when I can fit it in. Of course you’re welcome to go at your own pace and watch / read my analyses anytime, but I would like to arrange a Zoom call for subscribers at the end of part two and again at the end of the novel. That could be fun.

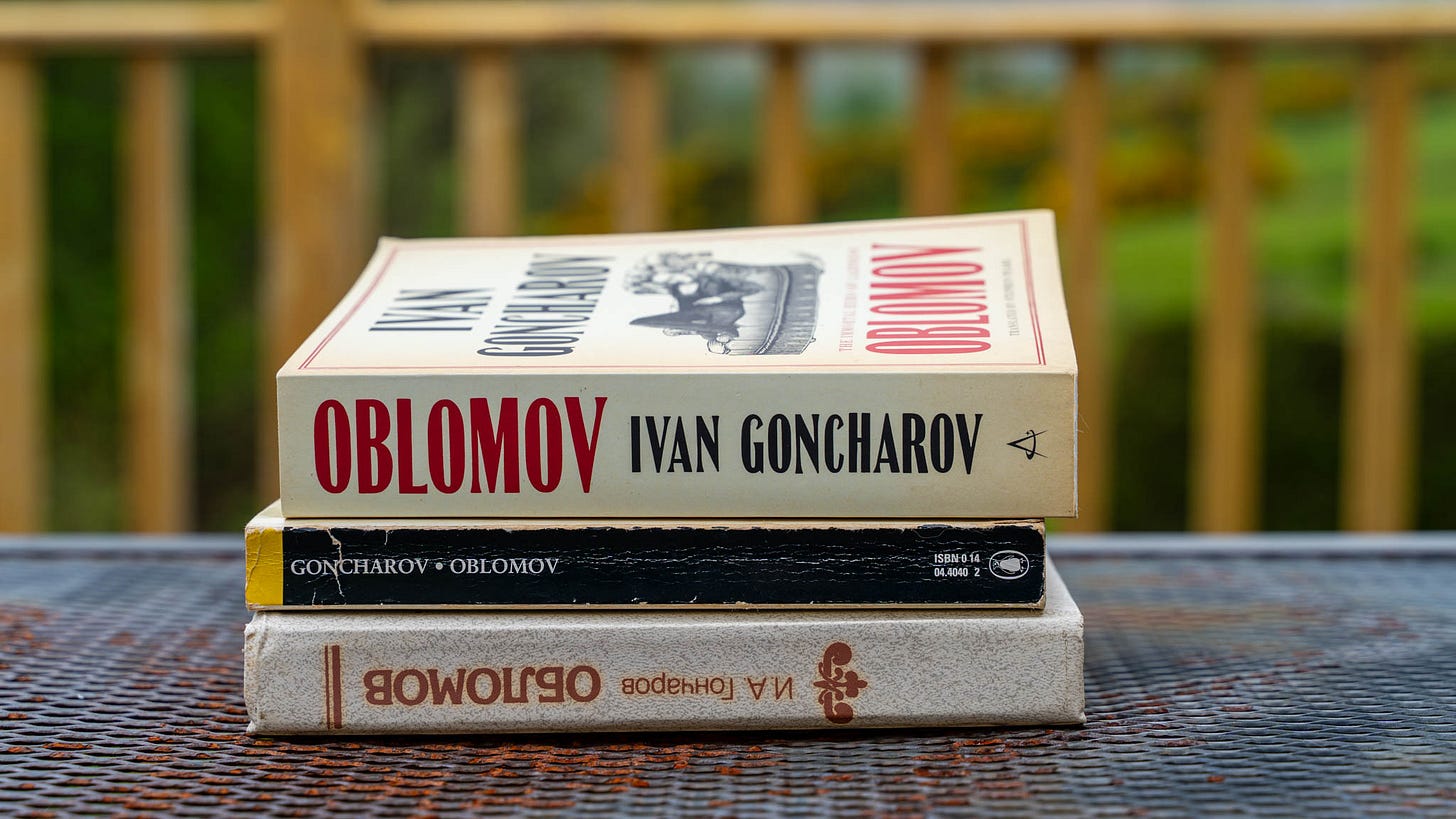

My history with this novel

I first read this in 1993/94 when I was in first year of my undergraduate degree in Russian language and literature at the University of St Andrews. It was the only essay I wrote over my four years at St Andrews in which I scored a mark over 70. Its title—What is Oblomovism and can it be cured?—was relatively easy to answer, unlike some of the more obscure questions I had to answer over the years. If you ask nicely I might even share it here!

I read Oblomov again in 2023, this time with knowledge and personal experience of autism and ADHD. It was super interesting to read the novel through that lens. It suddenly made even more sense why I related to this novel above all others that I read at uni. And that, dear reader, is why I love reading so much. This novel is universal. The condition of oblomivism—or oblomivitis—is not new and is still very much relevant. Maybe the Russians were just ahead in how they looked at psychology or how they depicted it in novels. Tolstoy was certainly a master of observing the human condition, as was Dostoyevsky. So the Russians took hold of the condition of oblomovism as presented by Goncharov and brought it into public consciousness. Medically speaking, it’s now called something else, of course—ADHD, autism, executive dysfunction. It’s perhaps a symptom of oblomovism that can get in the way of my writing bookish content when I’ve said I would, then spiralling down into low-mood and doom-scrolling. But you’ll be pleased to read that, in my essay back in the day, I concluded that it could indeed be cured. I’m not saying that it can be removed as a pathological condition; I’m saying that there are tools and strategies for managing it and achieving goals despite the condition, the -ism, the -itis. I’m sure we’ll learn more about that as we read the novel. In short though, the Beatles called it when they said all you need is love.

Chapter 1

So, all that said, here’s the recording I made after finishing chapter 1 this morning. Let me know your thoughts. I’d be really keen to hear views on neurodiversity and how you think the main character might be struggling with executive dysfunction.