Background Reading for The Master and Margarita

A short biography of Bulgakov and a brief history of the period to prepare for the novel in January.

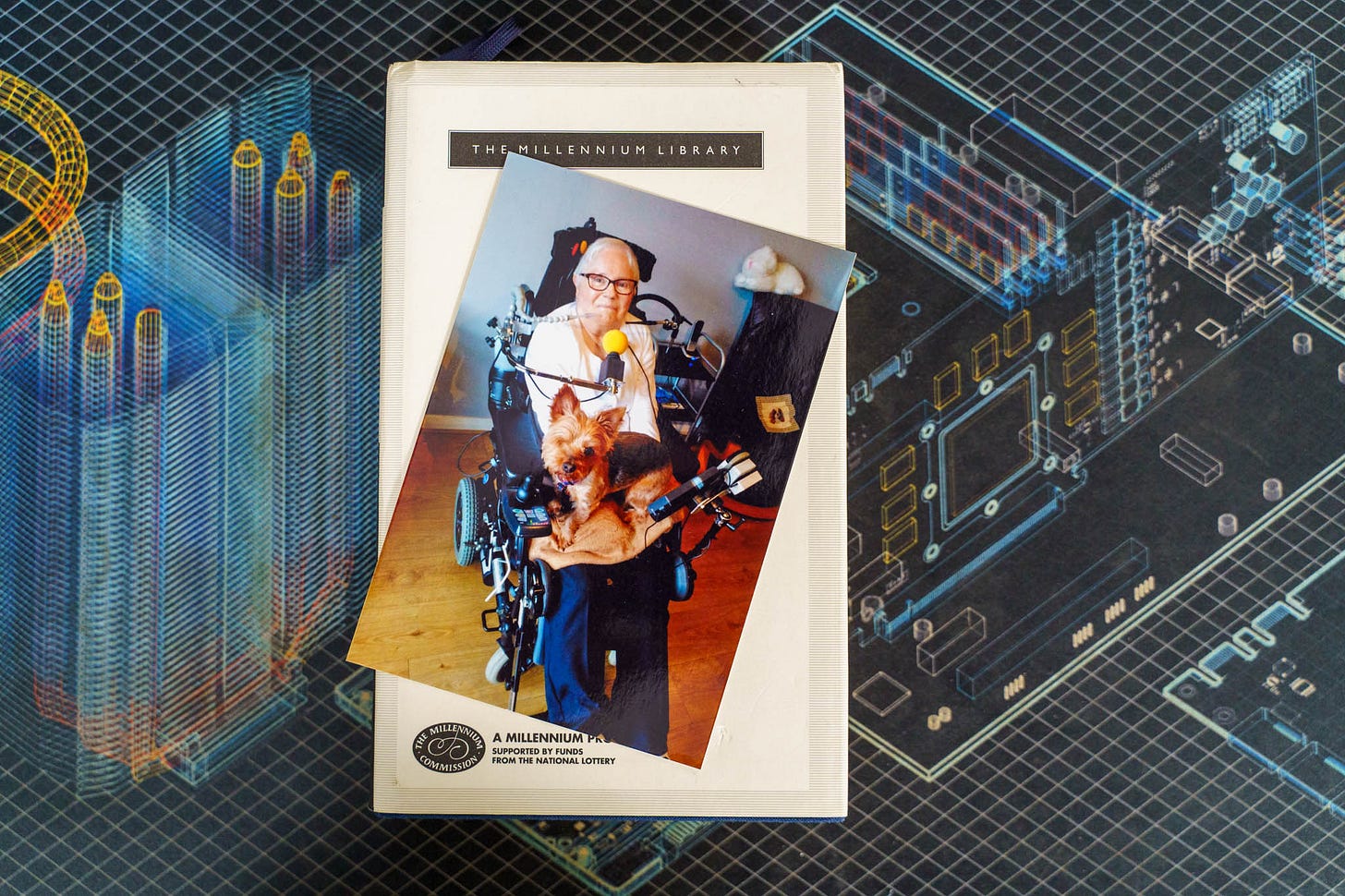

This will be my fourth time reading this novel and I’m beyond excited to be doing it with this group! As I said in the announcement post that went out to all my subscribers, it’s a novel that’s special to me because it makes me think of my late mum. I was reading it in the middle of the night after having woken up with a premonition. I was lying on the sofa, fully dressed with my book, when the hospital called with the bad news.

I thought you would find some background reading useful before picking up the novel. I read The White Guard, another of Bulgakov’s novels, in a reading group here in October, and I know some of you read it with me. I learned a lot about the author during that reading and it’ll stand me in good stead for this reading of The Master and Margarita.

Watch the video version of this post

Who was Mikhail Bulgakov?

Mikhail Afanasyevich Bulgakov (1891–1940) is one of the most compelling figures of twentieth-century Russian literature. Although The Master and Margarita is now widely recognised as a modern classic, Bulgakov didn’t live to see it published. The novel’s long and troubled history is set against the backdrop of Stalinist Moscow and the attendant pressures placed on writers during his lifetime.

Bulgakov was born in Kyiv, then part of the Russian Empire, into a cultured and educated family. He trained as a doctor and worked briefly in provincial hospitals during the First World War and the Civil War that followed the Russian Revolution. These experiences exposed him to human suffering, institutional chaos, and moral ambiguity, all of which later reappeared in his fiction in satirical and fantastical forms.

In the early 1920s Bulgakov abandoned medicine and moved to Moscow to become a writer. At first, the post-revolutionary literary scene was lively and experimental, and Bulgakov enjoyed early success with prose and plays that combined comedy, grotesque exaggeration and social critique. As Joseph Stalin consolidated power, however, the cultural atmosphere changed dramatically.

Stalinist Moscow and censorship

By the late 1920s and early 1930s, Soviet literature had been brought firmly under state control. Independent literary groups were abolished and replaced by official organisations such as the Union of Soviet Writers. “Socialist Realism” was declared the mandatory artistic method, requiring works to depict Soviet life as heroic, optimistic and ideologically sound. Satire, fantasy, religious themes and moral ambiguity were increasingly condemned as suspect.

Censorship operated in unpredictable and often arbitrary ways. Manuscripts were blocked before publication, plays were rehearsed and then suddenly banned, and writers were publicly criticised in ways that could destroy careers overnight. Bulgakov found himself particularly vulnerable. By the end of the 1920s, almost all of his work had been suppressed.

Unlike many writers of his generation, Bulgakov was neither arrested nor exiled. Instead, he endured enforced silence. Unable to publish and increasingly dependent on minor theatrical work, he continued to write privately, revising and rewriting what would become The Master and Margarita. The novel took shape over more than a decade, shaped by a fierce commitment to artistic freedom.

Moscow itself, the novel’s primary setting, was a city of contradiction. Grand ideological claims coexisted with fear, shortages, bureaucratic absurdity and constant uncertainty. Housing was scarce, denunciations were common, and truth was often whatever authority declared it to be. Bulgakov’s Moscow is fantastical and exaggerated, yet rooted in reality.

Publication and legacy

Bulgakov died in 1940, ill, exhausted and largely unknown to the reading public. The Master and Margarita appeared more than twenty-five years later in a heavily censored Soviet edition. Only gradually did fuller versions circulate, revealing the novel’s extraordinary range and ambition.

Today, the novel is read as both a work of wild imagination and a quiet act of defiance. Written without any expectation of publication, it insists on moral seriousness in a world structured around fear and compromise. Its famous claim that manuscripts don’t burn stands as both satire and a challenge.

Reading The Master and Margarita for the first time

If this is your first encounter with The Master and Margarita, it may help to release some expectations about how novels usually behave. The book opens abruptly, shifts tone without warning, and moves between satire, fantasy and philosophical seriousness with remarkable speed. Early confusion is not a failure of attention but part of the experience Bulgakov is creating.

Characters appear quickly, sometimes with little explanation, and the narrative leaps between different settings and even different centuries. Rather than trying to fix everything in place immediately, it is often more rewarding to read attentively but lightly, allowing scenes to register before worrying about how they connect.

Humour is central to the novel, though it is rarely gentle. Bulgakov’s comedy is sharp, absurd and frequently cruel, aimed at vanity, cowardice, greed and self-deception. Moments of farce often coexist with genuine menace, and laughter can turn suddenly into moral seriousness.

Religion and philosophy appear throughout the book, but they are presented through story rather than argument. No specialised knowledge of theology, Soviet history or Russian literature is required. What matters most is attention to questions of truth, responsibility and the consequences of refusing to speak honestly.

Above all, The Master and Margarita rewards patience. Some of its most moving moments arrive quietly and late. Reading the novel in a group allows its layers to surface collectively. Confusion, disagreement and sudden flashes of recognition are not obstacles here but signs that the book is doing its work.

Getting to know each other

Is this your first time with the novel? Or an old favourite you’re excited to reread? Something in between? Let me know in the comments! I’ll start a chat thread for subscribers too, so you can get to know each other there and let us know where you’re writing from.

Housekeeping

To join the read-along on 1 January, be sure to check your subscription settings and set the radio button to ‘on’ to receive the weekly posts in your inbox.

My announcement post includes the reading schedule, a list of the English translations I have, and a translation recommendation.

The Master and Margarita | Read-along, 2026

I’ll be reading this wonderful novel over January and February. This will be my fourth time reading this novel and I’m very excited about it! Weirdly, it wasn’t on any reading lists for my undergraduate degree at the University of St Andrews, but I read it anyway. It became an instant favourite.

See you in the book!

Your background post is immensely helpful - I've never read any of the famous Russian literature works (it feels pretty daunting) but I'm excited to stretch my reading capabilities as I read along

This one has been on my shelf for several months and I'm looking forward to reading it under your guidance. The October group read of The White Guard wetted my appetite for more of Bulgakov's work - thank you, Cam.