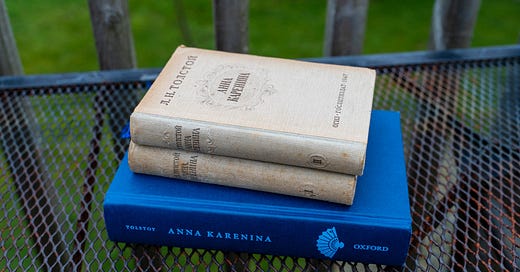

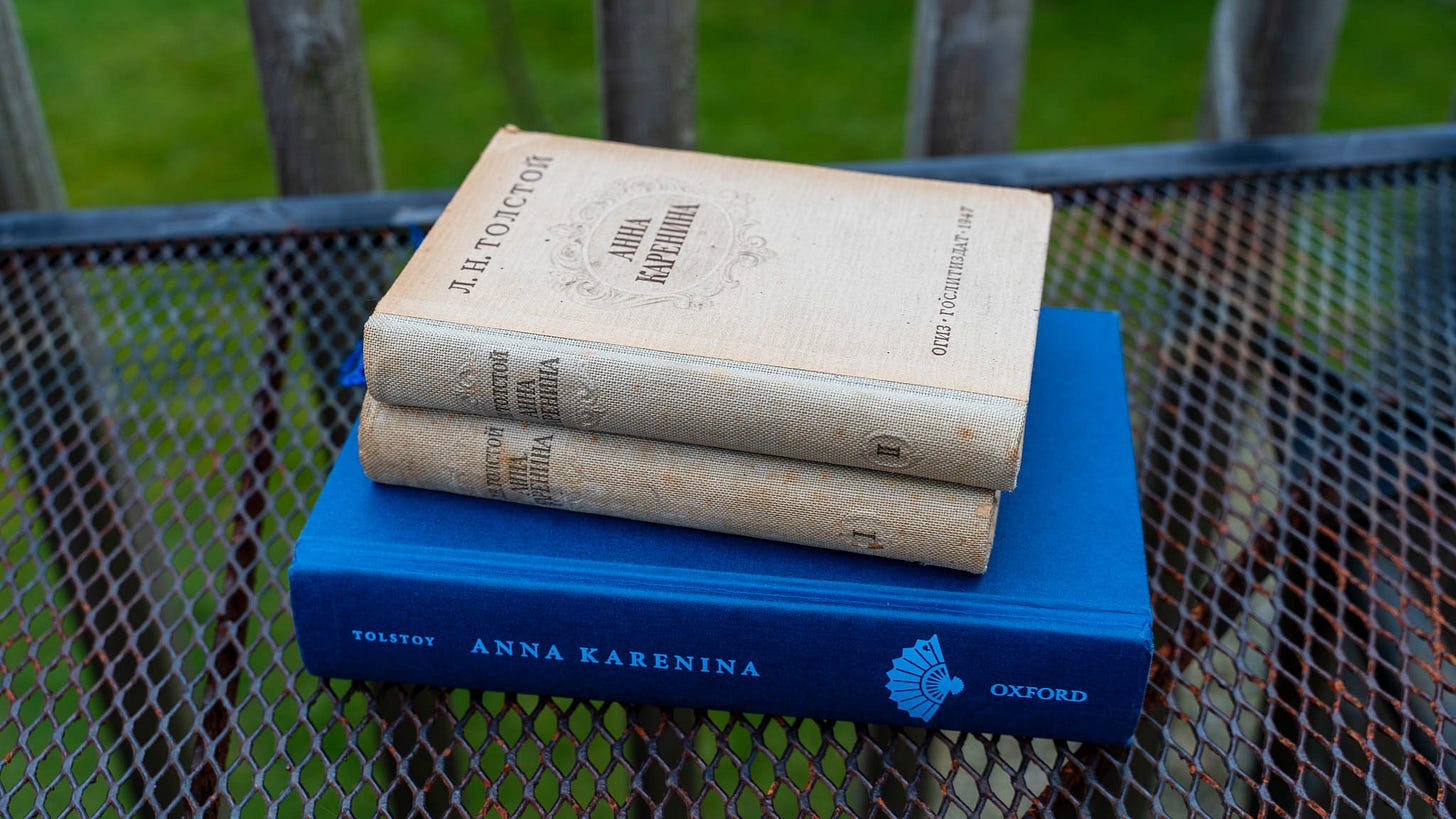

I’m reading Anna Karenina right now as part of

’s read-along. I was just reading a beautifully written chapter on the sofa—Part 1, Chapter 29 , where Anna’s on the train with her book after her first encounter with Vronsky—and my mind went back to the first time I read that novel. I was 22 and not long out of the army. I came out the forces on a medical discharge after two years of surgeries and recuperation following a climbing accident in the Lake District. I’d long known that the discharge was looming, so I spent my sick leave at high school getting the exams I needed for university entrance. That worked and I started a degree in Russian language and literature at the University of St Andrews in 1993. Talk about a fish out of water! On the language side, I was pretty strong, having aced my language training in the Royal Corps of Signals, achieving the prize for best linguist in my intake. Literature though? Nope! I really didn’t like it.I’ve always been a reader, but up till then it was mainly fantasy, science fiction and horror. I’d read lots of Stephen King, David Eddings, Tolkien and Terry Brooks. I was a fan of the Dragonlance series too, and my favourite series was Donaldson’s Chronicles of Thomas Covenant. So I was very much a genre fiction guy, and some of it quite juvenile.

Anna Karenina was one of the first books I read in my first year. I was not ready for this kind of literature. A quick glance at my first-year exam paper reveals that the reading list for that year comprised Chekhov’s Lady with a Lapdog, Gogol’s The Overcoat, Crime and Punishment, Oblomov, Asya, Zoshchenko’s short stories of the 1920s and White Guard. Somehow I managed to skip Asya and White Guard. Ironically, I started White Guard a few months ago and seem to have inadvertently given up on it. It’s on my list for 2005. Watch this space!

My first coursework essay was on Chekhov. It was handwritten and scored 57, not terrible. My professor’s comments:

Although it is not a brilliant literary essay, it is a start, and it will gradually get easier. Specifically, you need to stick more closely to the assigned question and not talk about other (irrelevant) matters, e.g. narrative viewpoint.

Seems fair. My not addressing the question was a pattern that took me a long time to figure out.

By the time I got to Anna Karenina, I’d switched to my Smith Corona word processor. I’m not sure why I didn’t use it for Chekhov, possibly because I read Chekhov in Russian and Anna Karenina in translation and I don’t think at that stage I had the Cyrillic daisy-wheel. Yeah, that was probably it.

The only memory I have of reading Anna Karenina in first year is of reading it on a dark Sunday afternoon in my room in my hall of residence. I have no recollection of what I thought of it, good or bad. The only novel from that year that I do remember enjoying was Oblomov, and even then enjoy is perhaps going a bit too far.

The essay title I answered for Anna Karenina was:

‘Don’t steal rolls.’ - Levin to Oblonsky. Is this the real message of Anna Karenina?

I scored a 58. Professor’s comments:

This last sentence is your only explicit attempt to tackle the question. You must in these essays do more than give information about plot and character in the text; you must discuss the question, assembling arguments (your own or those of critics) and presenting them. You do not, however, say anything that is incorrect about the novel. You do show considerable knowledge of the text.

Once again, the old not-answering-the-question trope. He was right though. It did get better, but not by much!

It’s interesting now that I’m in my 50s to be enjoying these 19th century Russian works as much as I am. I feel really drawn to them in a way that has surprised me, and not only to Russian literature but to English and American, too. Being part of the online book community is definitely a factor in that. It’s so good now to be able to see that five-year education in Russian literature at St Andrews as being something really valuable. At the time I didn’t understand that; I’d signed up for a language degree, not a literature degree, but as a single-honours student—the only one in my year, as it happens—I basically had no choice other than to take every literature module on the syllabus. I’m now grateful for that.

Now that I’ve started looking back at that period of my life, I’d like to write a larger piece covering the full five-year trajectory of reading literature, including during my year in Ukraine when I read a lot of literature, both Russian and English. If that’s something you’d be interested in, please let me know!

Your life is an exciting novel, a journey full of twists and turns.

What a magnificent essay and history of education, Cams. And you still have the assignment sheet, that's so wonderful. I haven't kept anything from my exams.

But three hours for three such complex questions is madness. I would have managed to answer only one in three hours at most. And some questions I wouldn't be able to answer at all now.